History of the Building

Tallinn Business Center | Harju 6, 10130 Tallinn

Harju 6 history of the Building

Harju Gate in the first half of the 19th century.

In the foreground, the Ingeri Bastion can be seen, along with a new fortress gate (the rampart gate) built in the 1760s, which was located on the site of the original Second Outer Gate. The roof visible to the right of the gate opening belongs to the main gate tower. In the foreground is the Lasteaed (Kindergarten), established in the early 1820s as one of the first public green spaces in the Old Town.

Graphic, 1833 — Adam, Victor; Hostein, Edouard.

The commercial building at Harju Street 6 in Tallinn’s Old Town indeed has a distinguished history and carries significant historical value. This building, like many others in the Old Town, is part of an area inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List and reflects Tallinn’s rich past and architectural diversity.

1361

The history of the building begins with the Harju Gate.

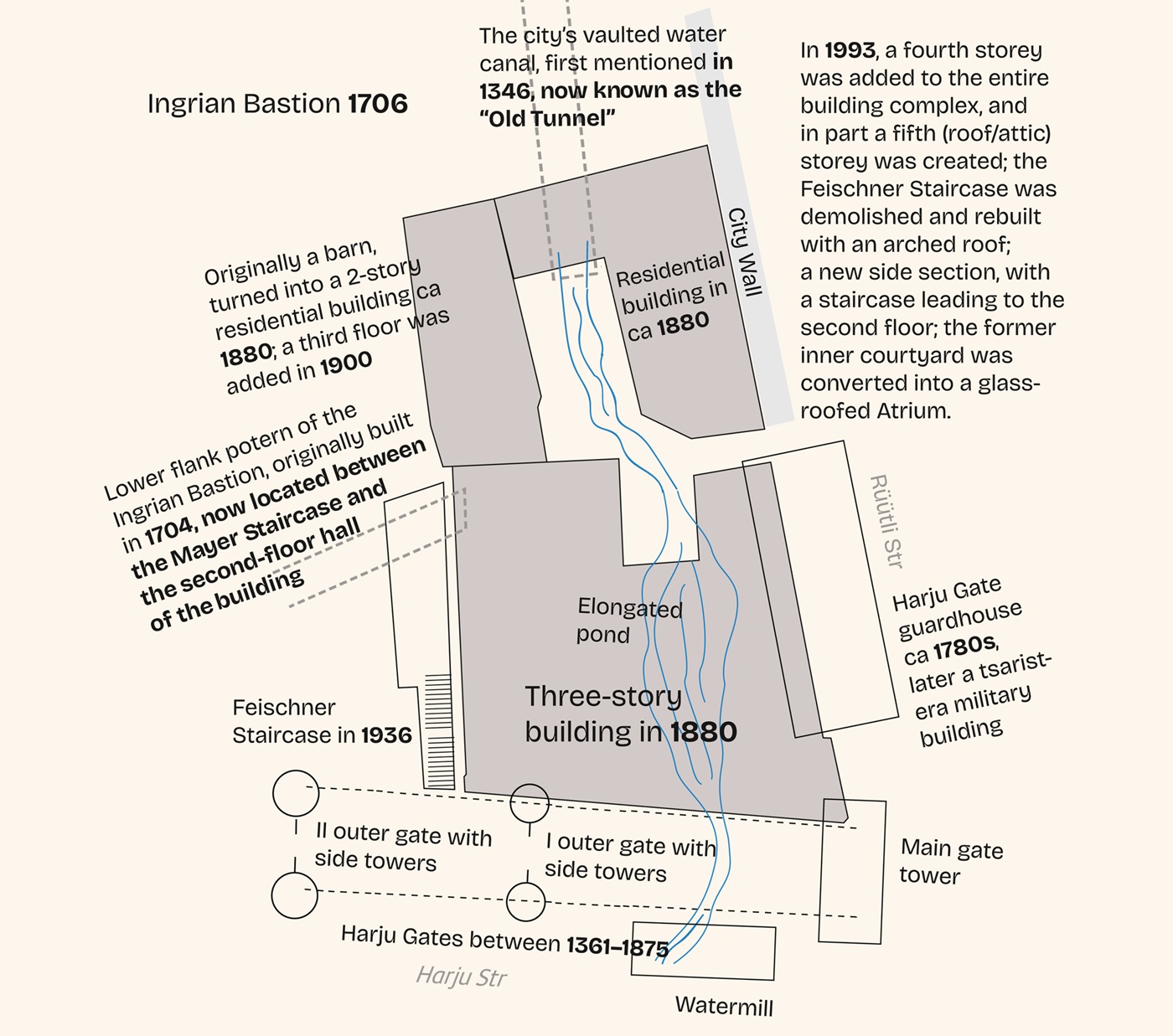

Harju Gate was part of the defensive system of medieval Tallinn’s city wall. It consisted of a main gate tower set within the city wall and the First and Second outer gates with their flanking towers. The former location of the main tower of Harju Gate is today occupied by the buildings at Harju Street 6 and 13, situated on either side of Harju Street. The gate is first mentioned in written sources in 1361. Harju Gate was partially reopened in newly rebuilt form only in 1767 as the “new” rampart gate. At the corner of Vabaduse Square, the lower part of the eastern tower of the Second outer gate of Harju Gate can still be seen today.

Some of the earliest major events took place by order of the Danish king Waldemar IV, who on 29 September 1345 granted the Tallinn City Council and townspeople the right to direct water from Lake Ülemiste into the city moats. For this purpose, in 1346 a water canal approximately 4 km long was built, with a limestone bottom and walls. The canal ended slightly west of Harju Gate, forming an elongated pond that in turn supplied a watermill constructed there.

Ingeri Bastion, 1706

In 1686, the Swedish king Charles XI approved a project for the fortification of Tallinn, according to which the Ingeri Bastion was built following the designs of Erik Dahlbergh. Present-day Harjumägi stands on the earthworks of the Ingeri Bastion. Drawings of the Lower Town fortifications show that in 1705 a canal originally constructed there was left uncovered. During the Great Northern War, in 1705, this section of the canal was converted into a vaulted tunnel, and the rampart of the Ingeri Bastion was expanded over it. It is likely that the canal was vaulted by the Tallinn City Council to ensure cleaner water, while the bastion itself was completed by the Swedes. The section of the Old Tunnel (Wana Tunnel) in its present form thus developed together with the construction of the bastion.

In 1706, the earthworks of the Ingeri Bastion on the side facing today’s Vabaduse Square were completed. The Harju 6 building now rests against this bastion structure on the Harjumägi side. During the construction of the bastion, a second vaulted passage was also built in 1704—the postern of the lower flank of the Ingeri Bastion, a covered connecting passage to the fortress through which the bastion’s artillery was supplied with cannonballs and gunpowder. Initially, the postern was made of wood; later it developed into a stone-vaulted passage, part of which has survived between the Mayer Staircase and the hall on the second floor of the building.

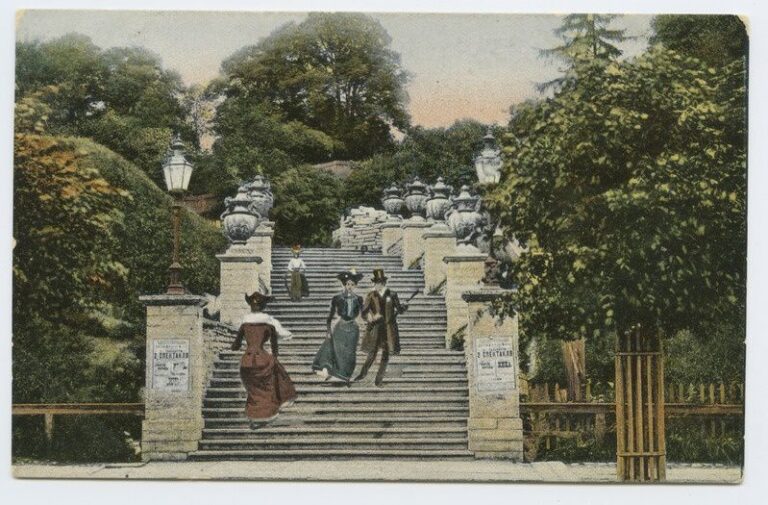

The Mayer Staircase

Carl August Mayer was a member of the Tallinn City Council from 1831 to 1860 and served as Mayor of Tallinn from 1860 to 1864. The staircase on Harjumägi built at his initiative bears his name. In 1864–1865, at his own expense, Mayer had a stone staircase constructed from the beginning of Harju Street to Komandandi Road in order to provide better access to the park planned on Harjumägi. To decorate the staircase, Mayer placed eight ceramic ornamental vases along it. In 1886, the broken vases were replaced with eight new cast-iron vases and two lanterns, manufactured at the Drümpelmann and Wiegand factory.

On his initiative, English-style public parks were laid out on the Ingeri and Swedish bastions between 1860 and 1862. At the same time, Komandandi Road was built through the bastion parks. The construction of the road was overseen by the Tallinn commandant (1856–1863), Lieutenant General Baron Alexander Woldemar von Salza, after whom the road was named.

1880

One of the prides of the Middle Ages on the site preceding our present plot was Harju Gate. After losing its defensive importance, the demolition of the gate structures began in 1862; the main gate was torn down in 1875. On the Toompea side, along Rüütli Street, stood the Harju Gate guardhouse, later a small army building, which for some time also served as the officers’ casino of the 90th (Onega) Division.

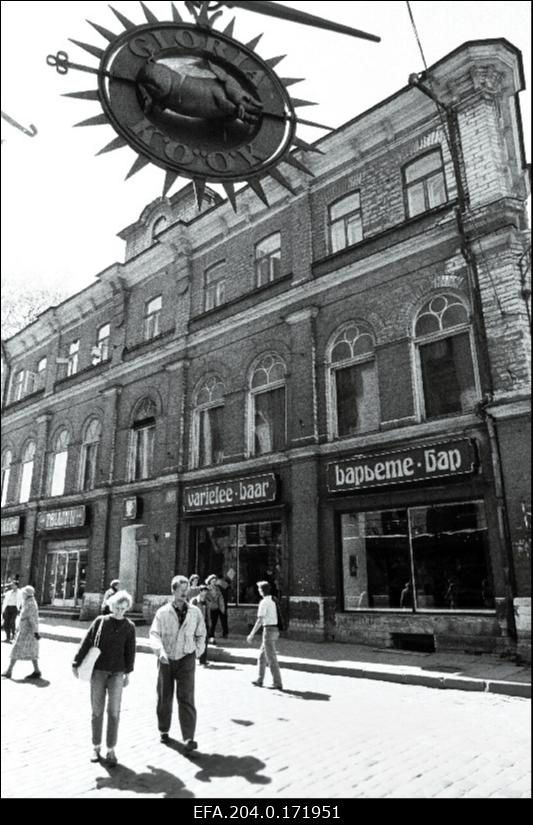

The demolition of the main gate was followed by a period of intense construction activity. The most notable project was a three-storey stone building commissioned by the merchant Alexander Ernst and designed by architect Rudolf Knüpffer, the construction of which began in 1879. The building directly adjoined the aforementioned state-owned building. From that period, the entire structure has survived to the present day, namely the Harju Street façade, where shops were planned on the ground floor. The second floor was distinguished by tall arched windows of luxurious apartments. On the third floor, where the living quarters were more modest, the windows were smaller and their arches lower. The building was roofed in 1880, as confirmed by archival documents and by the decorative plaques above the main entrance opening onto Harju Street. The left plaque reads “EDIFI-CATUM ANNO 1880”, and the right “No.608 II REV.ST.T. A.ERNST”, where after the property number the abbreviation denotes Tallinn’s Second City District, followed by the owner’s name.

At the same time as the main building, a simple granary was completed in the courtyard facing Harjumägi. A residential building was constructed against the city wall along Rüütli Street. Soon, a two-storey residential building rose on the site of the granary, and at the end of the century its new owner, Major General Baron Eduard von Maydell, received permission to add a third floor. The project was designed by architect Nikolai Thamm. Thus began the building complex that forms today’s Harju 6 property.

Harju Street (in German, Schmiedestrasse) was named after the historic Harju Gate. Harju Gate itself (Schmiedepforte, “Smiths’ Gate,” first mentioned in 1361) originally took its name from the so-called Smiths’ Street, which connected it to the Lower Town market square. In 1881, the watermill of Harju Gate was also demolished; part of the large rampart in front of the gate was levelled, the moats were finally filled in with earth, and the newly formed open space developed into the Hay Market (Heinaturg). Over time, this became Peter’s Square, named after the statue of Peter I, and today it is known as Vabaduse Square.

In 1913, Christian Rubin’s bookshop is recorded on the ground floor. In 1917, two important cultural-historical events took place in the building: the first Estonian bookshop was opened, belonging to the publishing house Varrak Ltd., and Tallinn City Second Real School moved into the building. From 1922, it was renamed the Tallinn Technical Coeducational Gymnasium, whose classrooms were located on the second and third floors. The composer Gustav Ernesaks also studied at this gymnasium. Between 1918 and 1927, the Tallinn City Boys’ Commercial School operated in the building.

During the Republic of Estonia, 1918–1940

In August 1917, the Maydell property was purchased by innkeeper Wilhelm Kirstein. In 1920, he submitted an application to enlarge the shop windows on the ground floor of the main building. The project was designed by architect Franz de Vries. Thus, the café “CAFE KIRSTEIN” was opened on the Harju Street side of the ground floor, initially consisting of only two medium-sized rooms. In 1922, the café expanded on the Vabaduse Square side into a two-hall establishment with a total of 200 seats. In the evenings, a respectable dance orchestra performed, and no alcohol was sold. In 1927, Kirstein continued energetically with renovations, this time applying for permission to remodel part of the main building along Rüütli Street. A notable innovation at the time was the installation of central heating throughout the entire building. Later in 1927, due to changes in his business affairs, Kirstein sold the café to the neighbouring bookshop, the publishing cooperative “Rahvaülikool.” The entire property was then acquired by the Merchants’ and Industrialists’ Cooperative, which opened the restaurant KÜBA in the main building. As the public tended to smile at the unusual name, a new one was adopted: SAVOY.

In 1929, permission was granted to build an external staircase on the Harjumägi side of the main building, leading to the second floor. The architect was Eduard Jacoby, and the client was now the cooperative “Rahvaülikool,” which had become the owner in the meantime. The construction was completed in 1930, and the new entrance proved to be excellent publicity for SAVOY.

Alterations continued in the building leaning against the city wall along Rüütli Street. In 1932, a hat factory moved into the second floor, where a steam boiler, electric motors, and other equipment were installed. The project was prepared by graduate engineer N. Kamõšhev. The Rahvaülikool also conceived the idea of establishing a cinema in the large building. The project was commissioned from Eduard Kuusik, but it was never realised. In 1933–1934, the café premises were already operating as the restaurant “Ampiir.” Thereafter, the rooms took on a more religious character when they were occupied by the Young Women’s Christian Association (then known locally as ENNENKAAÜÜ).

Major construction works were undertaken in 1936, when architects Eugen Benard and Viktor Tretjakovitš designed the so-called “long room” with a large kitchen on the second floor, next to the external staircase. In this same section of the building, two spacious halls were now planned for the second floor. The design and reconstruction costs were covered by confectioner Gottlob Feischner, who had decided to relocate his café here from the building opposite. The ceremonial opening took place on 17 November, with a total of 250 seats across both floors. At that point, the previously sole proprietorship had partially passed into the hands of the association “H. Feischner & Son.”

Gallery

The building at Harju Street 6 is an important landmark in Tallinn’s history and embodies significant cultural and architectural value, forming an integral part of the Old Town’s rich heritage.

Café Tallinn, 1940–1991

In 1940, the building was nationalised. After the war, the café “Tallinn”, operated by the Tallinn Trust of Canteens, Restaurants and Cafés, began its activities there. In 1945, the unused and unrepaired former shop and storage rooms of the “Rahvaülikool” at Harju Street No. 48 were allocated for permanent applied art exhibition spaces under the administration of the Applied Art Centre of the Estonian SSR.

In the second half of the 1960s, a new interior design for the café-bar “Tallinn” was completed. Interior architects Väino Tamm and Vello Asi did not limit themselves to adapting the existing interior but created an entirely new look for both the lower and upper floors. In keeping with the spirit of the era, the designers used the exposed limestone wall as a decorative element. Among the classics of the café’s furnishings were Vienna chairs, which had been brought there from the main building of the University of Tartu.

In 1969, the first variety theatre in the Soviet Union began operating in the renewed premises—the bar-variety “Tallinn.” The performances of choreographer Mait Agu, featuring dance, song, and even can-can numbers, were in no way inferior to the famous Parisian variety theatres. One may recall, for example, the French chansons sung by Maie Tõnso. Guests arrived from Moscow, Leningrad, and Finland to enjoy professional variety performances provided by artists from the Estonia Theatre. The variety theatre became a refined meeting place for higher society, and many received the news of its closure in 1992 with great sadness.

1990

Tallinn Business Center

Following Estonia’s restoration of independence, Tallinn’s mayor Hardo Aasmäe initiated a new chapter in the building’s history in the early 1990s by entrusting the renovation of the Harju 6 building to American investors. In 1990, representatives of the Tallinn City Government, the City Council, and American business circles discussed whether to renovate an existing building or construct a new one that would bring Western-style business to Estonia. Hardo Aasmäe and Kim Alan Williams, President of Texas International Lifestyles Inc., first signed a memorandum of intent, in which Harju 6 (then Café “Tallinn”) was one of five selected buildings. The American business representatives chose Harju 6 as their preferred option.

In 1991, a memorandum of intent was signed by Tallinn Deputy Mayor Irina Raud, John M. Battle, Director of the American consulting firm The AmSov Consulting Group Ltd., and Toomas Ando, Director of the Tallinn Old Town Foundation. Thus, the American–Estonian joint venture AS TBC was established, with equal shareholding between the Tallinn Old Town Foundation and The AmSov Consulting Group Ltd. As a result, a completely new level of office building was about to enter the real estate market in the form of the historic Harju 6 building.

The building was renovated in the final decade of the 20th century according to a project by AB “Wana Tallinna” (architect Galli Holland). During the renovation, the Swedish-era vaulted water tunnel—the à la carte Wana Tunnel—and the postern of the Ingeri Bastion flank were restored; the latter housed the Karoliina mulled wine bar for many years. The American-style elements that further enhanced the design were introduced by architect Kim Williams. These included a curved roof projection over the staircase leading to the second floor on the Harju Street side, a transparent plastic-glass roof over the inner courtyard (the Atrium), creatively designed handrails for the staircases leading to the fifth floor, stainless-steel tubular railings for the terraces, and more.

The first phase of the building—the Päikese Gallery, designed by Rain Pikandi—opened on 1 June 1993. The spacious premises were occupied by Nordisk Interiors, a Swedish furniture sales and interior design company. Among the first tenants were also the Italian gold and jewellery company AS Kuldsõrmus and the British insurance firm Lowndes Lambert Overseas Ltd. The building, popularly known as the “American Business Center,” was officially opened on 31 July 1993. On the same day, the Embassy of Japan began operating in the building. The doors were also opened by Europe’s largest Irish pub, George Brownes, the wine shop Finest Vendors, offering Estonia’s most expensive wines, the gold business Centrumix, and the Estonian company Eesti Õliliit. Thus, the Tallinn Business Center was born. In November 1993, Arno Kannike became the director of the Business Center. A skilled communicator, he successfully bridged relations between the city and the American owners while simultaneously offering tenants innovative interior solutions and new opportunities unprecedented on the market.

The 1990s were also characterised by the building’s reputation as a financial centre, hosting banks such as SYP, KOP, Siberian Commercial Bank, and Merita Bank. Among business tenants were the Toyota representative office, the MaxMara fashion store, Restaurant Viktoria, and Fazer’s à la carte restaurant Wana Tunnel.

21st Century, 2002–2024

In 2002, the city announced a public tender for the sale of the building. The EBS Group, previously active mainly in education and training and led by owner Madis Habakuk, won as the core investor and purchased the building from the City of Tallinn. In addition to business interest, Habakuk had always considered it the most beautiful building in Tallinn.

Arno Kannike continued as managing director, leading the building until the end of 2023—remarkably, at the age of 80. The most enduring tradition he established during his 30-year tenure was the annual Children’s Christmas Party. Tenants included Ernst & Young Estonia, the Hugo Boss fashion store, and Handelsbanken. Businessman Rein Kilk developed the unique revue theatre Bel-Etage with distinctive wall decorations in the former 1960s cabaret hall. Some companies grew so large that the premises eventually became too small for them, and well-known names gradually changed.

Over the course of its history, the building has borne many names. During this period, another was added: the House of Embassies. Since 1993, the Embassy of Japan has been located there; in 1998, the Royal Norwegian Embassy; in 2013, the Embassy of Greece; and in 2020, the Embassy of North Macedonia. It is also undoubtedly a house of cafés, a tradition dating back to the previous century. The entrepreneurial spirit is embodied in the building’s name, Tallinn Business Center. Arno Kannike upheld the tradition of marking the beginning of the seasons with brass band concerts at George Brownes Pub and later at Stereo Bar. Outdoor concerts were held on Harjumägi at Varblase Café. During his tenure, he also published four issues of the Tallinn Business Center newspaper.

In 2008, the building’s façade received a lighting design based on a concept by De Napoli Agency, highlighting the distinctive character of the 1880 building even more prominently in the evening hours. In 2010, De Napoli designed an illuminated glass display for the street wall between the Mayer Staircase and the building, which became known as the Culture Display. Estonian museums present posters of their current exhibitions there.

In 1999, the Japan–Estonia Friendship Society, operating on the island of Hokkaido, donated 200 sakura (Japanese cherry) saplings to the Republic of Estonia. The trees were cultivated in two nurseries by dendrologist Aino Aaspõllu. On 7 May 2004, nineteen young cherry trees were planted on the Ingeri Bastion in front of the Consular Section of the Japanese Embassy. The planting was attended by Chargé d’Affaires a.i. Toshiko Shimizu. The entire initiative was organised by the Friends of the Tallinn Botanic Garden Society.

2025…

THE BUILDING CONTINUES TO LIVE ITS NEW HISTORY AND AN INTERESTING LIFE…

The texts draw on the writings of historian PhD Heino Gustavson, Arno Kannike, and various online information sources. Contributions on Tallinn’s early history were provided by Ragnar Nurk, City Archaeologist of Tallinn.

The overview was compiled by De Napoli, 2025.